Dawn Treader by Chronotope Project is one of the best electronic music releases of 2015. Progressive Rock Central talks to multi-instrumentalist and composer Jeffrey Ericson Allen, the artist behind the project.

Why did you name your current endeavor Chronotope Project?

The term “chronotope” was coined by the Russian philologist Mikhail Bakhtin, from the Greek words for time (chronos) and space (topos), and refers to their confluence in works of art and literature. It felt like an ideal descriptor for the music I compose, which has strong reference points to spiritual, literary and mythological/ archetypal memes. There is an additional sense of the transcendence of space and time, an endeavor to discover and express the universal which lies behind particulars.

What drew you to music?

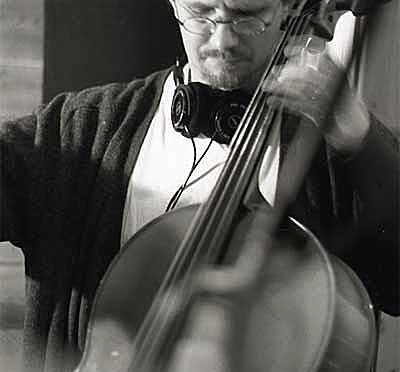

I’ve been a musician all of my life, starting at the age of eight, when I began cello studies with my grandfather. When I was young, there was always music playing in my family home, mostly classical. I longed to know where it came from, what it was, how I could be a part of it. I cannot remember a time when my head was not filled with melodies, rhythms, and musical gestures. Although I am also dedicated to language, philosophy and literature, music begins where words fail, emotionally moving, intellectually stimulating, connecting directly with the body. Music is my lifetime lover, an unfailingly inspiring muse, the water in which I swim.

What do you consider as the essential elements of your music?

My style, while still falling roughly into the ambient or space music genre, might more accurately be described as “contemplative art music.” Form figures more prominently in my work than in the generally more diffuse, stream-of-consciousness pieces of my fellow ambient composers (not a criticism–I love much of this type of music as a listener). You can find many classical forms present in my work: theme and variation, passacaglia, rondo, sonata. Increasingly, I have been tightening up on form and relying less on pure texture or ambience.

In my current phase of creative work, I am making pieces with relatively complex, almost orchestral textures. As to elements, there is frequently an underlying sequenced ostinato figure, an element of “fire,” scintillation or almost molecular quickening. This lends some suggestion of the Berlin School style to the work.

The “earth” element (besides its selective appearance in acoustic and sampled percussion) is established with a foundation in the bass, presented either with a layered drone or a bass line suggesting the underlying harmonic progression. This may be felt as a slowly undulating shift or oscillation between stable and unstable tones of the tonic.

Harmonic sonorities floating over these bass tones, painted with various layered pads, are frequently colored with suspended fourth or unresolved seventh and ninth chords. These kinds of harmonies evoke mystery, and a feeling of searching or longing in the composition.

My melodic lines commonly develop in very long, slow phrases, with substantial “breathing” between them. A second or third line often plays in counterpoint, weaving common melodic motifs in dialogue with the central melodic voice. These constitute, together, what I think of as the “water” or emotional element to the piece.

The element of air or ether appears with the atmospheric textures that surround and permeate all of these other layers. These textures vary from natural soundscapes, such as wind and water, to more abstract synthetic ambient sounds that identify the work in the ambient electronic genre.

Who can you cite as your main musical influences?

Individual composers who have been deeply influential include Erik Satie, Klaus Schulze, Brian Eno, Robert Rich, Maurice Ravel, Arvo Pärt, Ralph Towner, and J.S. Bach. Various world music traditions have also informed much of my music making, including Indian raga, traditional Japanese music, West African rhythms, and Balinese gamelan, to name a few. Over the years, I have made a fairly considerable study of musical scales and modes as they appear both in Western and non-Western musics, and these inform a good deal of my compositions.

Tell us about your first recordings and your musical evolution.

An early acoustic /electronic album was “Vanish into Blue” (1992). This eclectic album bridged new acoustic, world and space music styles, and featured acoustic cello, sax, tabla, and silver flute as well as an array of electronic instruments. It was featured several times on Hearts of Space and received very favorable reviews. I composed for, arranged and recorded two albums with the acoustic ensemble Confluence, “Sanctuary: Romances for Guitar and Cello,” and “Amber Moon.”

While these albums also involved a certain amount of synthesizer sweetening, they were primarily acoustic. I played cello, recorders and keyboards on these albums. I also gained some facility with production techniques and mixing, as I was the primary recording engineer on these projects.

An acoustic / electronic CD of music I composed for the mask drama The Descent of Inanna appeared in 1998. This was an exploration into mythological / archetypal imagery that has become a persistent theme throughout my later work.

As Chronotope Project, I released four albums prior to signing with Spotted Peccary Music: “Solar Winds,” “Chrysalis,” “Event Horizon” and “Dharma Rain.” All of these recordings are available through CD Baby and Bandcamp, and continue to receive periodic airplay.

These albums have traced a progression from more traditional space music to the more eclectic and classically inspired style of the present, involving increasingly subtle use of texture, more counterpoint and other classical forms and procedures, and a more unified personal style.

Do you ever take your music to the stage or is Chronotope Project a studio concept?

At this point in time, Chronotope Project is strictly a studio-oriented proposition. Given the number of simultaneous tracks involved, I would be hard-pressed to recreate any of my compositions on stage. I won’t discount the possibility of another incarnation of my work that more readily permits of live performance, but for the moment, no real-time presentations are being offered.

You play acoustic and electronic music instruments. What instruments do you play and which do you like best?

Cello is my primary instrument, and will always be my first love in music. Ironically, it has played–thus far–a fairly limited role in Chronotope Project. I have a beautiful 1917 Steinway grand piano, which I love to play, and study regularly with a teacher. I also have a nice collection of flutes, recorders and Irish whistles, which do figure prominently in recent recorded works, as well as a Japanese thirteen string koto, the long zither which appears on one track (“Basho’s Journey”) on “Dawn Treader.”

I play a variety of hand percussion instruments, including djembe, frame drum, dumbek and the very versatile hybrid acoustic / electronic Korg Wavedrum.

Bells,Tibetan bowls, zils and chimes are also an important part of my acoustic toolkit, as I prize their crystalline tone and quality. I have been making increased use of the 24-stringed harpejji, an instrument akin to the lap steel guitar, played primarily by tapping on its frets. That instrument figures prominently in several releases to come.

What type of keyboards did you use at the beginning of your career?

My first electronic keyboards, acquired in the early 80s, were a Sequential Circuits Six-Trak, an Arp 2600 analog synthesizer, and a little later, a Korg T1 workstation (the only one of these vintage instruments I retain). I learned something from each of them, including elementary sound design, and each afforded me many hours of exploration and discovery. The Arp, in particular, required me to learn the basics of analog synthesis, as sounds are built up by connecting various modules with patch cords and adjusting knobs and sliders.

When digital synthesizers supplanted analog synths, something was gained and something lost, and the current renaissance in modular analog synthesis reflects a recognition of the remarkable versatility of these instruments.

When I have more cash on hand, I plan to put together my own modular rig. It’s tremendous fun, and appeals to my nerdy side, but the primarily, it’s the rich palette of analog sound that appeals to me now.

What keyboards are you currently using? Do you still have some of your earlier keyboards?

My flagship synthesizer is the Haken Continuum Fingerboard, which features a soft neoprene continuous-pitch playing surface and lends the possibility of much expressiveness to synthesizer performances. It is prominently featured on all of my recordings as Chronotope Project. But these days, most of my “keyboards” are virtual instruments, of which I have a great many. I do keep the Korg T1 mostly for its lovely weighted action, as well as a Yamaha S90ES, which also has a good feel, and many useful sounds as well. A Roland JV-1010 sound module provides a large variety of sounds and samples, and until just recently, I used an Oberheim Matrix-1000 for analog fattening.

And what type of effects or other electronic devices do you use?

All of my effects, too numerous to mention, are virtual now–no outboard reverbs, delays or compressors are in my rig. I do enjoy using a Korg “Kaosilator Pro” as a midi controller for various purposes, and employ a number of iPad apps as well.

How do you see the progressive electronic music scene in the United States?

It’s a mixed bag–both in terms of quality of work and diversity of style–and with the wide availability of outstanding production platforms and instruments, the various genres involved (IDM, ambient, electronic art music, etc.) are likely to diverge to the point at which the only thing they share is some of the means of production. It’s very hard to get perspective on something that is changing so rapidly, but it is an exciting time to be involved in electronic music.

Commercial radio and the mainstream music press ignore most electronic music except for electronic pop. How do you seek exposure for your music?

There are a number of outstanding radio programs and podcasts (such as Hearts of Space, Echoes, Star’s End, StillStream, Ultima Thule, and Galactic Travels) that feature ambient and electronic art music, several of which are widely syndicated and have large numbers of dedicated listeners. Exposure on these programs has widened my audience considerably.

Spotted Peccary Music, to which I have signed for at least six records, has a dedicated promotional team that makes and maintains contacts with radio producers, distributors and media, and does an excellent job of launching new projects and placing CDs in distribution.

At my end, the promotional work is more focused on social media and keeping my listeners informed through newsletters, and in many cases, personal letters.

Promoting this kind of music is not always easy or straightforward, but the listeners of this genre are highly motivated and do much on their own accord to stay informed. I communicate directly and personally with many individual listeners, and while this is more time-consuming than a “mass-media” approach, I value this correspondence very highly, and consider many of my listeners to be friends, not just faceless “fans.”

I would rather that my music connect very deeply with a few listeners than to have a huge fan base of casual listeners. Fortunately, this type of music cultivates very intelligent, immersive listening, and I have been richly rewarded for the time I have taken to address single listeners.

If you could gather any musicians or musical groups to collaborate with whom would that be?

Brian Eno to produce. Robert Rich as a collaborative composer. Steve Roach for sound design and analog sweetening. Ralph Towner to teach me his harmonic language. The ghost of Erik Satie for spiritual advisor and drinking buddy.

Do you have any upcoming projects to share with us?

My next album with Spotted Peccary Music is entitled “Passages.” This one is ready for mastering, and will be released sometime this year.

Other forthcoming titles with SPM are “Ovum,” “The Gateless Gate” and “The Cloud of Unknowning.” Substantial work has been done on all of these projects, to be released in roughly that order.

I am also planning a piano-based album, based on the musical language of Erik Satie, that will also feature cello and some electronic sweetening. This recording will be acoustic-oriented, and possibly appear on another label, depending on how well it may or may not fit into the Spotted Peccary array of genres.

—

Artist Website: http://www.chronotope-project.com