Yes: What a splendid name for a prog-rock group, for any music group. Positive, upbeat, optimistic, life-affirming, “Yes we can!” as Barack Obama said in his successful presidential campaigns. Yes, we can, indeed, as in: Twenty-minute pieces of music that are dynamic all the way through? Yes, we can do that! Resurrect ourselves from the muck and mire of commercial music pressures? Yes, we can do that too! Multiple times! Split into two versions of Yes, but then bring those versions together for an album and tour? Yes, well, yikes, kind-of… And looking towards the future…but that’s a question best left for the conclusion of this tribute.

Yes’s eponymously titled debut in 1969 features none of the lengthy epics for which they eventually became known. But there are surprising numbers of hints at what was to come. Complex, memorably melodic compositions that feature distinctive harmonizing, especially between lead vocalist Jon (John in 1969) Anderson and bass player Chris Squire (R.I.P.) are just a part of it.

“Survival” and their cover of the Beatles’ “Every Little Thing” open with hard-edged instrumentals, similar to how “Heart of the Sunrise” and “Siberian Khatru” would start a couple of years later. Peter Banks’ sinuous little touches on acoustic and electric guitar around the edges of “Beyond and Before,” “Every Little Thing” and “Survival” foretell Steve Howe’s comparable approaches to “Roundabout” and numerous other pieces including on their latest, The Quest.

Meanwhile, Jon Anderson’s vocals soar midway through “Sweetness” in a manner certainly prophetic of the “Soon” passage in “The Gates of Delirium.” And most fascinating is how the instrumental buildup for “Every Little Thing” leads into the Beatles’ tune. The logic is very similar to the middle of “The Ancient,” part four of Tales From Topographic Oceans. There, the return to a galloping part of the introduction after the “Nous sommes du soleil” section leads into one of Steve Howe’s most epic guitar solos. Bottom line, if you’re a big Yes fan but haven’t heard their first recording yet, you’re in for a real treat.

Ditto for Yes’s second studio workout, Time and a Word (1970), even though there are still no epics. However, the frantic nature of many of the compositions, made all the more so by occasional full-orchestra injections (not to happen again until Magnification), give the feeling that Anderson, Squire and company are lumbering around like a pregnant mother well into her eighth month: child and parent alike are so uncomfortable they’re ready for birth already, in this case of tunes that break the seven-minute barrier. Cases in point: “Then” features one of Anderson’s wistfully uplifting refrains plus a hard-edged instrumental break full of Squire’s cutting edge bass work. But the understated conclusion feels incomplete, doesn’t even include one last run of that awesome refrain. The noisy finish might as well have had an UNDER CONSTRUCTION sign hung on it.

Meanwhile, the verses for “Astral Traveler” are essentially theme variations on the verses for “Then”; one can almost imagine these two tracks united, with the title track the peaceful “Soon” after the storm, tacked on at the end. And indeed, it does conclude the album right after “Astral Traveler” (which also incidentally includes a fantastic mid-section that foretells Steve Howe’s “Wurm” on album three, including a signature bass guitar ascent from Chris Squire).

Which brings us to The Yes Album (1971), introducing Steve Howe to replace Peter Banks on guitars. Running over nine minutes, opener “Yours Is No Disgrace” is longer than anything on the first two albums, a characteristic it shares with two other tracks, “Starship Trooper” and closer “Perpetual Change.” “Disgrace” is an eclectically complex composition, reflecting significant input by all members. Keyboard player Tony Kaye continues to favor gritty, muscular Hammond organ in lieu of orchestral-sounding synthesizers such as the Mellotron, and Jon Anderson’s vocals inform this monumental track with classical music sensibilities, being a series of theme variations.

As with the other long tracks, the arrangement of “Disgrace” has plenty of room to breathe so that while it is energetic all the way through, it doesn’t sound frantic. While “Starship Trooper” is perhaps most noteworthy for Steve Howe’s “Wurm” conclusion, wherein the listener can easily imagine said starship ascending to the heavens, the two-note opening is especially interesting as a signature move also heard in later Yes epics. It is freighted with grandeur in a way that recalls the opening to Strauss’s “Sprach Zarathustra” used for the opening of the sci-fi film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

On The Yes Album, Steve Howe got to show off on his own in a live version of his fun, country-music-inflected acoustic guitar hoedown, “The Clap.”

But for Yes’s next effort, Fragile (1971), every member had their short moment in the solo sun, including new keyboard player come over from The Strawbs, Rick Wakeman. Steve Howe’s “Mood For A Day” is especially notable in that regard, this time more Spanish-flavored than hoedown-leaning. But the real stars of the show are the three lengthy compositions, starting with the eight-minute “Roundabout.”

Bookended by more fabulous acoustic guitar work by Howe, “Roundabout” features an especially infectious refrain that Kool And The Gang might have borrowed from for their ubiquitous party song, “Celebration,” nearly a decade later. Ridiculously, the radio version edits out the tribal-rhythm mid-section that adds so much power to the full version.

“South Side of The Sky” also features a strong mid-section, underpinned by a haunting piano melody. And in the ten-minute closer, “Heart of the Sunrise,” Rick Wakeman introduces the Mellotron to a Yes composition for the first time, in most dramatic fashion. It seems to launch the rhythm section into space, as though musically depicting the solar sailing vessel on the album cover, Roger Dean’s first for Yes. Like “Disgrace,”

“Sunrise” is also a very eclectically arranged composition, making many surprising twists and turns that culminate forcefully in Jon Anderson’s “feel lost in the city” near the conclusion.

No more short moments for individual show-offs on Close To The Edge, released in the fall of 1972. Featuring for the first time Roger Dean’s iconic Yes logo in addition to more fantasyland paintings, Edge answers the question, “If a ten-minute composition, why not an eighteen-minute composition?” And that’s what we have for the title track opener, the only track on side one of the original vinyl. A flurry of nature sounds resolves into an instrumental introduction harder edged, harsher than the Mellotron-drenched start of “Heart of the Sunrise.” It leads into a sonata structure often found in movements of classical music symphonies, though including vocals rather than being totally instrumental (perhaps the key innovation of progressive symphonic rock).

There are two statements of a lengthy, convoluted series of melodies, the second statement a variation on the first, followed by a mellower mid-section, followed by a furious variation on the concluding theme of the instrumental introduction, and climaxing with a third statement of the convoluted melodies, including a very moving, chord-resolving resolution that ties the mid-section refrain together with the “close to the edge” refrain, and dissolving away into the nature sounds that opened the piece.

“Close to the Edge” is a creative triumph I believe will stand the test of time for centuries to come. Ditto for the ten-minute “And You And I” that opens side two. Somewhat similar structurally to “Edge,” has to be one of the greatest love songs ever, including a dramatic, mellotron-powered mid-section.

Incidentally, live versions add a slight tweak that brings this masterpiece to even greater heights: Namely, Steve Howe’s electric guitar is made to sound like an eagle taking love’s flight into the stratosphere. The bit-shorter closer, “Siberian Khatru,” has that frantic feel like much of Time And A Word that hints at Yes once again feeling a bit constrained.

Sure enough, Tales From Topographic Oceans answers the question: If one side-long composition (on vinyl), why not four? Oceans is actually one piece in four movements, again mimicking a classical symphony though twice the length of many symphonies, along the lines of a few symphonies by Gustav Mahler. Inspired by the four shastras of the Hindu faith referring to what is heard, what is remembered, what is ancient, and what are the rules, Oceans sprawls out in ways that reward repeated listens. Ironically, percussionist Bill Bruford left Yes prior to its recording, feeling he had already gone as far as he could with the group, to be replaced by Alan White, who previously recorded with John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band.

“The song that has been left for us to hear,” as Jon Anderson put it, “The Revealing Science of God” opens Oceans with Anderson’s stream-of-consciousness meditations leading into the reigning anthem of part one (revisited in celebratory fashion during part four). There are echoes of “Close To The Edge,” but this is an even more complex, if more leisurely developed stretch of music. Steve Howe gets in some transcendent guitar figures, Rick Wakeman lathers on the Mellotron in spots, Alan White (RIP) adds tastefully restrained percussion (holding back his real firepower for parts three and four), and Chris Squire (also RIP) underpins it all with his typically smoldering bass guitar, ready to erupt whenever necessary. The one small blemish in this entire masterpiece: the restatement at the conclusion of earlier melodies brings nothing new to the table, theme-variation-wise, even though the resumption of Anderson’s stream-of-consciousness for the final moments does create a nice dramatic sense of anticipation for what is to come.

In my estimation, Parts Two and Three, “The Remembering” and “The Ancient,” are two of the most under-appreciated progrock epics ever. “The Remembering” makes a slow burn to a finale every bit as moving as the conclusion to “Awaken” a few years later, and Wakeman’s Mellotron washes effectively invoke the oceans of this album’s title (as much as he was bored with this particular effort). Meantime, “The Ancient” carries the listener deeper and deeper into a primeval past until boiled down to a simple infectious folk tune carried on Howe’s acoustic guitar and more of Anderson’s distinctively spacey vocals.

The concluding “Ritual” is a grand finale in every best sense, especially noteworthy for a string of vocal melodies in the first half that flower one after the other, until building to a recap of the opening passages that set the stage for yet another brilliant electric guitar freakout by Howe. And the peace-after-the-tribal-storm vocals at the end, concluded by an ominously majestic theme variation, couldn’t have been more full of grandeur, truly one of the great ends to any progrock piece, and probably an inspiration for the finale of “The Truth Will Set You Free” by The Flower Kings.

One short year later, 1974, with keyboard player Patrick Moraz from the one-album wonder, Refugee, replacing Mr. I-just-don’t-get-the topographic-oceans-shtick Rick Wakeman, Yes released the at-times frenetic Relayer. The album title, recalling a passage from part two of Oceans, Relayer similar to Close To The Edge consisted of one side-long track followed by two nine-minute pieces.

The 22-minute Gates Of Delirium weaves classic Jon Anderson vocal passages towards a lengthy instrumental freak-out meant to portray war, followed by the peace of “Soon.” This particular epic feels like Yes suffered from a fever, then broke into a beautifully relieving sweat. All too “soon,” though, “Sound Chaser” resumes the overheated vibe, albeit temporarily relieved by a wonderful mini guitar concerto mid-section mostly composed by Steve Howe. After that, the listener is more than ready to go “sailing down the calming streams” of the gently meditative, if still satisfyingly complex and infectiously tuneful, “To Be Over.”

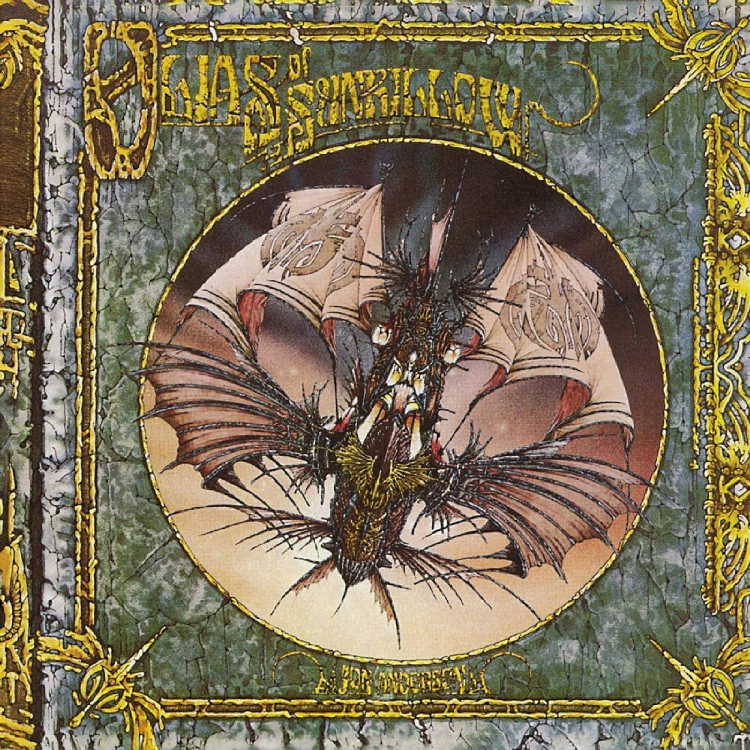

And that was it for Yes for a couple of years, while members took time out for some especially noteworthy solo albums. Among them, Jon Anderson’s fantasy concept work, Olias Of Sunhillow, might as well have been a Yes album with its typically-well-constructed, upbeat otherworldly nature.

Patrick Moraz’s concept work, emblazoned with what looks a bit like a golf ball on a tee, suggests that he contributed heavily to the frenetic nature of Relayer, just a brilliant, energizing blend of symphonic progrock with Brazilian jazz and folk rhythms, his solo masterpiece.

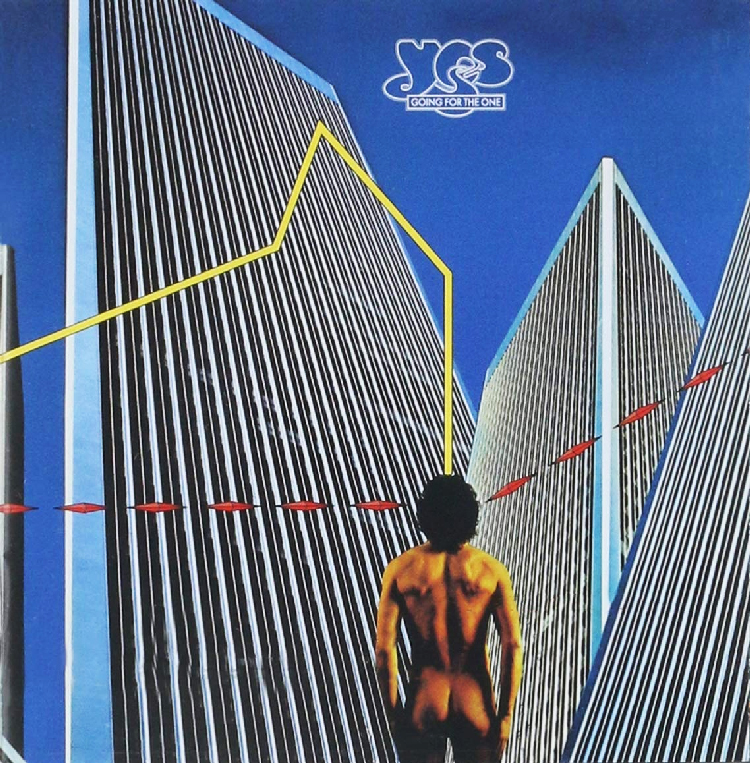

Back in the recording studio, under very murky circumstances Rick Wakeman returned to the fold, and Patrick Moraz was shown the exit despite having already contributed to composition of the new effort to be entitled Going For The One. For the first time since Fragile, there were pieces that didn’t break the nine-minute barrier, including the fun title track.

As Jon Anderson explained at the time for Circus magazine, the group was ready to take it easier for a while, not always shoot for the epic stars. But that didn’t preclude “Awaken,” a fifteen-minute track that sounds like a succinct distillation of everything Yes attempted previously. Wakeman added some especially tasty bits on pipe organ for the mid-section buildup, and the resultant climax before the heavenly coda is as wildly uplifting as any climax of their prior epics.

Not so uplifting was the 1978 follow-up, Tormato. “Future Times/Rejoice” gets things off to a wonderful start, the “rejoice” part especially containing complex guitar, keys and percussion interplay. But after sounding like the group was embarked once again on one of its fantastically lengthy and inspiring epics, the opener ends all too soon.

There’s plenty of nice music here; the seven-minute closer (longest track), “On The Silent Wings of Freedom,” is another succinct distillation of what they took close to twenty minutes to accomplish on “Close To The Edge.” However, when Anderson sings, “Don’t Kill The Whale,” one has to wonder if he isn’t also lamenting the commercial recording industry’s pressure during the late seventies for bands like Yes and Genesis to kill off long music forms.

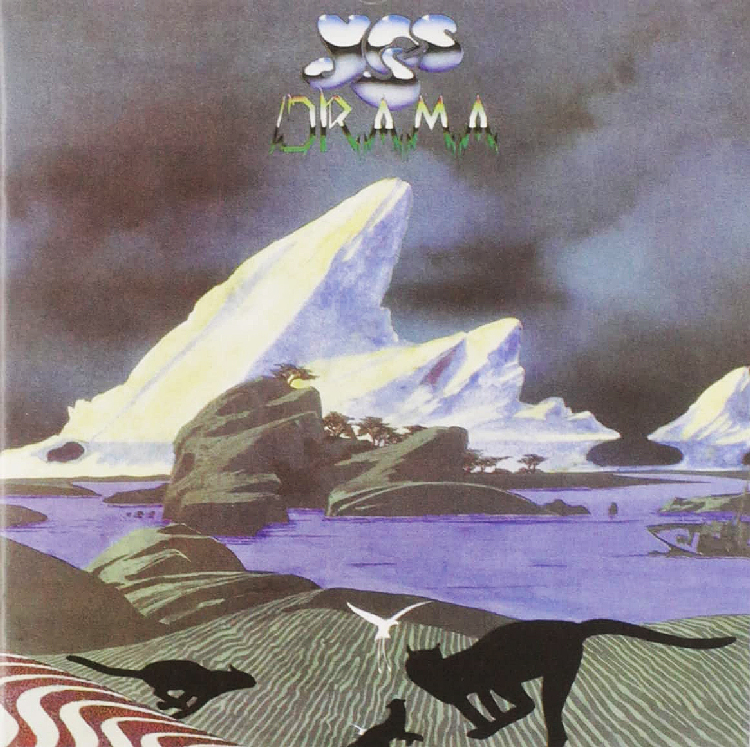

The Drama that followed in 1980, after Buggles pop stars Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes made up for Anderson and Wakeman bolting the group, still sounds a lot like classic progrock Yes, but for me a certain sadness hangs over it.

The ten-minute opener, “Machine Messiah,” has the darkest, gloomiest vibe of any Yes track, ever. As cool as the sludgy, plodding, Mellotron-drenched opening theme feels, it could have originated from Black Sabbath. And Jon Anderson’s spacey, make-me-one-with-everything lyrics are sorely missed, especially in the nonsensical “Into The Lens” even though the music itself feels like vintage Yes. Only “Does It Really Happen?” fully captures the uplifting spirit of earlier work, nearly a lesser sequel to “Starship Trooper.”

Saddest of all, the manic spirit of the five-minute closer, “Tempus Fugit,” reminds me of department stores near closing time playing fast music to encourage shoppers to hurry up and leave. Closing time for progressive symphonic rock, so hurry up and leave!

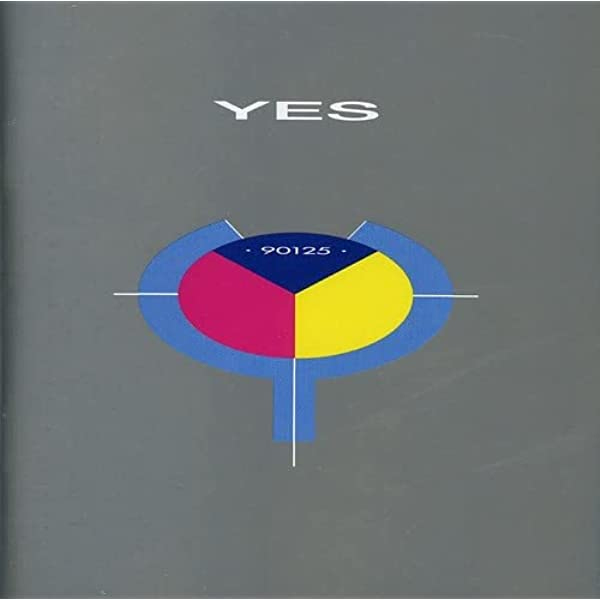

…which is what guitarist Steve Howe did before the next recording, while original Yes keyboard player Tony Kaye rejoined for what I find the group’s second most disappointing effort, 90125, released in 1983.

Lead-off track “Owner of a Lonely Heart” for which it is best known shares one similarity with “Roundabout”: it features a unique, playfully catchy riff. But whereas “Roundabout” takes us on an involving journey, “Owner” is static. Fun music, for sure, and the same as other tracks such as “It Can Happen,” certain Yes-sounding creative intricacies are folded in. But the exhilarating sense of adventure feels squelched. And ironically, nowhere is this more evident than on the longest track, the seven and a half minute closer, “Hearts.” Essentially an extended ballad, its refrain, to twist around certain lyrics of “Roundabout,” comes out of the sky and just sits there, static, very little transcendent feel in either its arrangement or execution.

Four years later, a tumultuous recording process produced this version of the group’s second effort, Big Generator. Intriguingly, Generator creeps back towards the original epic spirit of Yes, but that makes many of its tracks all the more frustrating. Opener “Rhythm of Love,” for example, includes a refrain full of desperate yearning as musical as any prior Yes refrain, plus a short but also very classic Yes musical vocal mid-section, but then the song decays into endless repetition for its conclusion.

The one track that finds classic Yes fully revived is the seven and a half minute “I’m Running,” replete with theme variations, some distinctive Hammond work by Tony Kaye, and a striving for transcendence in the concluding rehash of a Caribbean-sounding melody.

Based on the commercial success of 90125, lead vocalist Jon Anderson reportedly had ants in his pants to nudge Yes back in more adventurous directions. Mission partly accomplished with Generator, but not enough. As a result, Anderson reunited with Rick Wakeman, Steve Howe, and Bill Bruford, with King Crimson member Tony Levin filling in on bass, to more fully eschew commercial viability in favor of a return to the progrock frontier. The result was the 1989 Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe, complete with a Roger Dean painting, and three tracks in the nine to ten minute range. I.e. a Yes album by any other name.

“Themes” opens with Anderson’s declaration he’s through with the commercial recording industry, at least for then. “Be gone, you ever piercing Power Play machine…” What follows are cutting-edge progrock tracks such as “Brother of Mine” with its cinematically sweeping opening vocal among many other delights (Steve Howe’s epic electric guitar recap of that opening melody always leaves me teary-eyed), the Caribbean-meets-progrock joy of “Teakbois” (including a hint at one of the following track’s melodies), and the space-meets-grit cosmic in-your-face of “Order of the Universe,” segueing into the hope for the future of “Let’s Pretend.” Note also needs to be made of “Birthright,” about the tragic legacy of nuclear bomb testing, made all the more moving by Rick Wakeman’s majestic keyboard washes.

This wink-wink version of Yes quickly got to work on a sequel, but in one of the more insane commercial recording industry contortionist acts, they ended up joining forces with the legally official version of Yes, still including Chris Squire, Alan White, Trevor Rabin and Tony Kaye. The result was Union in 1991, what could also have been named Big Mess-enator. For sure, it opens with a terrific track, “I Could Have Waited Forever,” nearly seven minutes of vintage-sounding Yes that could have been left over from Fragile. It’s the longest piece, but it’s also arguably the only fully realized piece; many of the shorter ones that follow feel like cut-outs disunited, if you will, from epics that will never be, especially the three-minute “Dangerous.”

1994’s Talk saw the Tevor Rabin version of Yes reunited for a surprisingly strong recording, also the last involving keyboard player Tony Kaye. “The Calling” is another terrific opener, with a definite country rock flair, and featuring an awesome electric guitar flight by Trevor Rabin during the mid-section, this time sounding inspired by George Harrison. But unlike on Union, strong tracks follow, most notably Yes’s biggest epic since “Awaken,” the three-part “Endless Dream.”

A powerful wakeup-call leitmotif recalls earlier ones for Topographic Oceans and “Starship Trooper,” rounded out by a spacey mid-section, complex vocal passages, and a satisfying, mellowed-out conclusion full of choir.

Two short years later, and wowee, the Yes combo that produced Topographic Oceans and Going For The One released two double albums, two Keys to Ascension, one right after the other. One half concert recordings, the other half focused on new studio efforts, there was a clear effort to reconnect with their epic selves, albeit with mixed results. The nineteen-minute “That, That Is” generally succeeds in its lyrical reaching-out to people suffering too much to have time for starship trooping, and the seven-minute “Bring Me To The Power” is a vintage Howe-Anderson collaboration.

But the eighteen minute “Mind Drive,” while it does have its moments, sounds only partially realized; the closing passages, especially, just don’t cut it. If the group felt too insecure about the strength of their new material to release them on their own from the get-go, rather than sneaking them in on live recordings of their classics, one can’t help but feel they should have fermented them a while longer. Of course, financial necessity might not have granted them that luxury.

In any event, with Rick Wakeman’s departure for the fourth time, replaced by Billy Sherwood, 1997 saw the release of my number one pick for biggest disappointment, biggest “no” by Yes: Open Your Eyes. The problem isn’t that the longest tracks only run six minutes; some excellent symphonic progrock pieces run even shorter than that, such as “Can-Utility and the Coastliners” by Genesis. And the group’s musical genius for imaginative melodies still shows up on practically every track. No, the problem is that every composition, every single composition feels static, plenty of frills but zero substantial development. Where their earlier ten-to-twenty-minute epics seemed to fly by, such tracks as the six-minute opener, “New State of Mind,” feel like they go on forever, to no good purpose. Twenty minutes of jungle ambience randomly interspersed with chorales from some of the lyrics experimentally concludes this recording, as if the group sensed something lacking.

1999’s The Ladder represented a major rebound for Yes. The nine-minute opener, “Homeworld,” is anything but static, building to a glorious finale followed by a gentle coda a la “Soon,” if not quite as grandiose.

“Lightning Strikes” is a fun, Caribbean-infused romp complete with horn section that segues into the percussion-heavy “Can I?” that itself segues into “Face To Face” for an okay conclusion to this unexpected medley. And the nine-minute “New Languages” near the end is another satisfying mini-epic. All is not completely well, however.

“Finally” is yet another more recent Yes tune that sounds decapitated from some awesome progrock epic that will never be. The first half of this six-minute track is nevertheless full of life-affirming power in the best Yes tradition, while the second half spaces out with tacky sexual innuendo (“I can feel the rain coming…”), and begs for a more energetic conclusion, but alas… And a few tracks such as “To Be Alive” have that static quality so typical of Open Your Eyes. More often than not, though, The Ladder is solid Yes, promising better music to come.

2001’s Magnification generally fulfills that promise. Due to a scandal, Yes was down to a quartet (Anderson, Howe, Squire and White) with no keyboard player. So they brought in film score composer and big Yes fan, Larry Groupé, who for only the second time in Yes’s studio recording history had them employing a symphony orchestra.

Groupé actually did more than simply orchestral arrangements; he added his composing touch to several of the pieces, sometimes with terrific results, such as in “Give Love Each Day.” Among other successful tracks, the ten-minute, percussion-heavy “Dreamtime” is one of the more experimental efforts Yes has recorded since Relayer, and the other ten-minute track, “In The Presence Of,” builds and builds to the sort of stirring epic sweep of “Awaken” and other classic Yes compositions, if a bit mellowed out. The title track, for me, is one of the few disappointments, with its clunky transition from each verse to each refrain, and an overall simplistic structure despite its seven-minute length. Again, though, Magnification is a stirring success, hopefully not Yes’s last…

…which brings us to latter-day Yes since a health crisis temporarily sidelined Jon Anderson. His input is sorely missed on their last three studio recordings (well, three and a half if you include the four Oliver Wakeman compositions on From A Page (2019). Fly From Here from 2011 supplies perhaps the most dramatic case in point. The title track, at nearly 24 minutes, is the single longest Yes piece, ever, thinking of Topographic Oceans as four movements. And the first eight minutes provide a rousing start, including an exultant refrain as stirring as any in the Yes music canon. The remainder, however, sounds tacked on, a couple of songs not all that spectacular on their own, plus a short Steve Howe instrumental, “Bumpy Ride,” that is a pale shadow of the epic struggle depicted midway through “The Gates of Delirium.” A recap of the stirring “Fly From Here” refrain closes out this patchwork with no special twist added as found in all prior Yes fifteen-to-twenty-minute epics.

Jon Anderson knows how to add the secret sauce to give Yes’s epic progrock compositions a holistic feel. Yes just is not Yes without him, as well-intended as have been his vocal replacements, Mystery’s Benoit David on Fly From Here and Jon Davison for Heaven And Earth and the most recent The Quest. Exhibit One for my contention: Jon Anderson’s 2020 solo release, 1000 Hands, Chapter One. Exuberant, featuring an adventurous blend of diverse musical sensibilities with an always-urgent feel, this is the true Yes spirit, especially in the two eight-minute tracks, “Activate” and the title track. So much happens inside these two pieces alone, they require several listens to digest.

“Activate,” especially, feels like a lit fuse that goes off with several big bangs during its closing minutes. Folk music one minute, classical music the next, unexpected bursts of everything from gospel choir to steel drums, and how special that Yes stalwarts Steve Howe and the late great Chris Squire make guest appearances, in addition to Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson’s wild flute work on “Activate,” among numerous other delights.

Rick Wakeman employed lots of great ideas in his recent instrumental album about Mars, and so I say unto the group that calls itself Yes: bring Anderson and Wakeman back into the fold, and allow Anderson to bring along a few hundred of his friends that were involved in recording 1000 Hands, and then record something special that leaves the solar system behind! You can do it! Yes!!!!!

In January 2023, Yes announced that Warner Music Group’s Global Catalog Division acquired the recorded music rights and income streams from YES’ Atlantic Records era catalog. The deal includes iconic albums such as Fragile, Close to the Edge, and Relayer. The full purchase includes 12 studio albums, as well as live recordings and compilations.